As previously seen in “Part One” of this series, the European Union’s approach to succession and inheritance matters has undergone a significant evolution with the introduction of the EU Succession Regulation, commonly known as Brussels IV.

This groundbreaking regulation, which came into effect across most of the EU in 2015, signifies a fundamental shift in how transnational inheritance cases are managed, marking a departure from the traditional reliance on nationality as the key determinant in succession matters. The regulation aims to address the complexities and challenges that arise in the context of global mobility and diverse familial structures, providing a more streamlined and unified system for dealing with estates that span across national borders.

Now that we recollected what was seen on our previous article, let us delve specifically into what is regulated by the EU Succession Regulation.

Applicable Law & Choice of Law

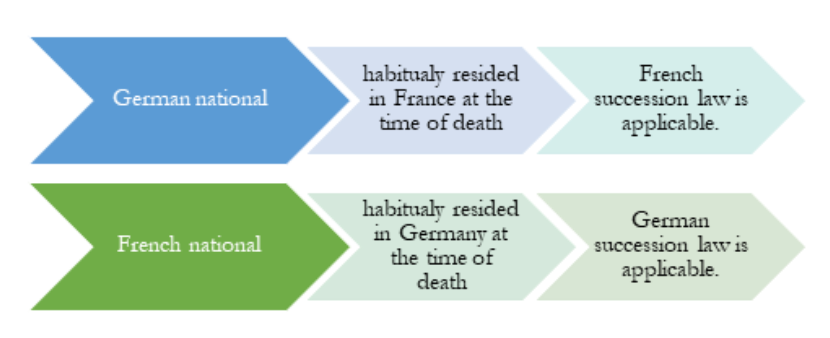

This regulation primarily focuses on determining the applicable law in cases of international inheritance, marking a departure from previous practices where nationality often played a central role. Under Brussels IV, the law applicable to a succession is primarily the law of the country where the deceased had their habitual residence (and not the deceased’s nationality) at the time of their death – in accordance with Article 211 a rule that applies to the entire succession, encompassing both movable and immovable assets (the single scheme principle).

For example:

However, it is not always that simple to determine one’s country of habitual residence. For instance, we could have a German testator that moves to France in order to work there for a long period of time, but still maintain a close and stable connection with Germany or we could even have a testator that has never really had a permanent location in which he resided, e.g. a Dutch testator that alternated between significant periods spent in the Netherlands and Spain. No definitive conclusions can be drawn for these cases, in which we may use the testators’ life overall circumstances, such as the duration and regularity of their residence in a particular country or where the central hub of that individual’s family or social interactions predominantly takes place.

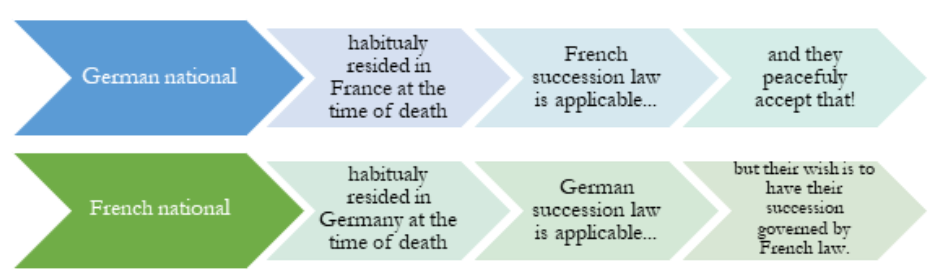

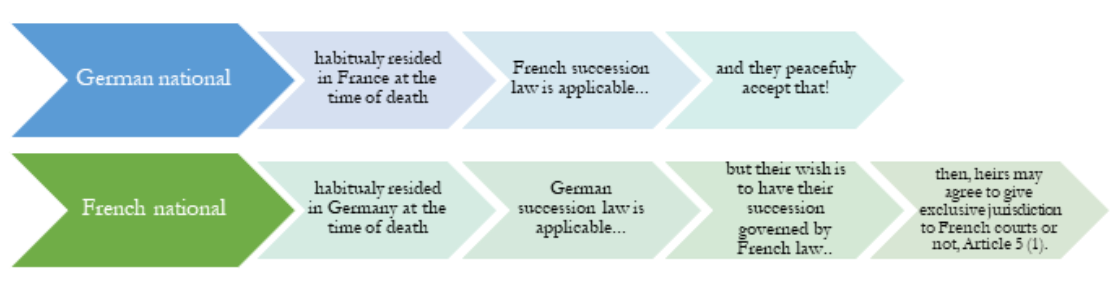

In addition to specifying the applicable law based on habitual residence, Brussels IV allows individuals the prerogative to choose the law of their nationality to govern their succession, as seen on Brussel’s IV Article 222. So, we face a new possibility:

This choice, which must be expressly declared in a legal document such as a will or inheritance contract or clearly apparent from the terms of such dispositions. This prerogative provides individuals with greater control over their succession (increased party autonomy), especially in situations where the habitual residence is ambiguous or complicated. It is important to state that if a deceased had chosen the applicable law to their succession prior to August 2015, that choice shall remain valid, provided it meets the conditions stipulated in Chapter III or if it is valid in the eyes of Private International Law statutes that were in force – in the State the deceased had their habitual residence – at the time of the choice (Brussels IV, Article 83)3.

Competent Jurisdiction

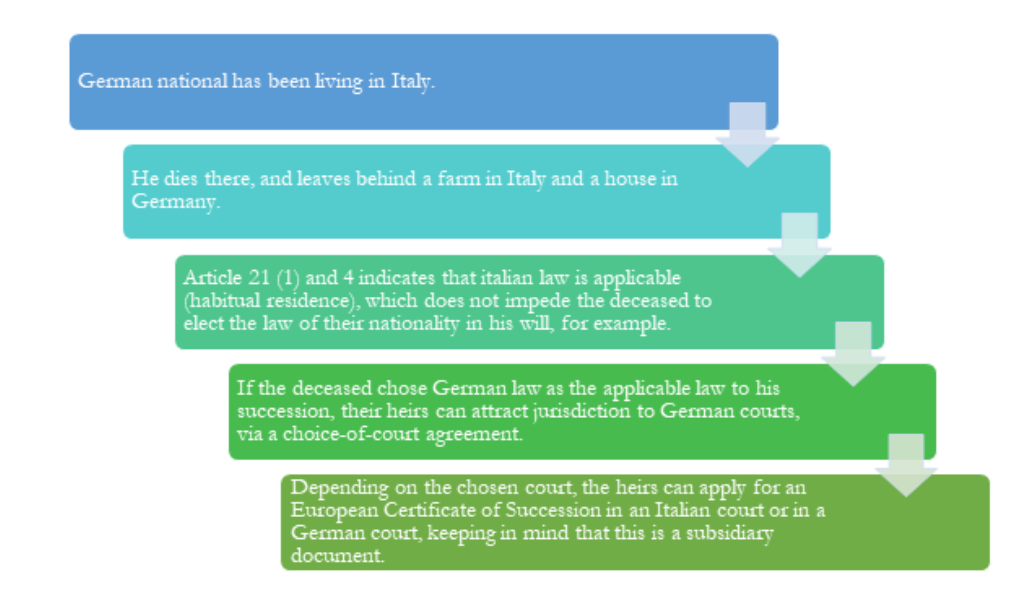

The regulation also addresses jurisdictional issues in succession matters. Generally, the courts in the country of the deceased’s habitual residence at the time of death are granted jurisdiction. However, the regulation provides for a scenario where, if a valid choice of law was made, jurisdiction can be transferred to the courts of the deceased’s nationality by the parts of the proceeding (in this case, the heirs), by concluding a choice-of-court agreement, offering a level of flexibility and convenience, all while granting an increased level of party autonomy to, both, the former testator and their heir(s), per Article 54.

Therefore:

European Certificate of Succession

A notable feature introduced by Brussels IV is the European Certificate of Succession (Article 62 et seq.). This certificate simplifies the administrative process in cross-border successions, serving as means to verify an heir’s status and rights to the estate throughout the EU. It eases the process of settling international estates by providing a standardized, and almost universally accepted document. It is important to point out that the European Certificate of Succession’s use is not mandatory, as per Article 62 (2) of Brussels IV; therefore, it does not replace documents such as national certificates of inheritance (e.g., German inheritance certificate), acting as a supplementary inheritance document.

Brussels IV and Pre-existing international agreements

Furthermore, the regulation is designed to coexist with existing international agreements, as per Article 75 of Brussels IV5.

A good example is the “German-Turkish Succession Agreement”, as it contains provisions on international jurisdiction and applicable law – that differ from what is seen in Brussels IV – which do not apply the single scheme principle. So, instead treating movable and immovable assets the same way, the “German-Turkish Succession Agreement” treats them separately regarding the determination of the competent jurisdiction and applicable law. For immovable assets (real estate) the applicable law is the law of the place where the asset is located (lex rei sitae), and the same goes for determining the competent jurisdiction. But for movable assets, on the other hand, the applicable law is the law of the deceased’s nationality, with jurisdiction lying within those same courts.

All in all, this means that specific bilateral agreements continue to influence succession cases under certain circumstances, ensuring respect for valid international legal arrangements made prior to the EU Succession Regulation.

In synthesis…

Overall…

The EU Succession Regulation, or Brussels IV, marks a transformative step in the management of international succession cases within the European Union. By harmonizing the approach to determining applicable laws and jurisdiction in transnational inheritances, it has substantially reduced the complexities and legal ambiguities that previously plagued such cases.

The regulation’s emphasis on habitual residence as the primary criterion for determining the applicable law, coupled with the option for individuals to choose the law of their nationality, represents a progressive shift towards increased flexibility and autonomy in succession planning. Additionally, the introduction of the European Certificate of Succession is a pivotal development, streamlining administrative procedures and ensuring uniform recognition of heirs’ rights across the EU.

This regulation not only simplifies the process for handling cross-border estates but also demonstrates the EU’s commitment to adapting its legal frameworks to the realities of an increasingly mobile and interconnected populace. By respecting existing international agreements, Brussels IV also shows a thoughtful integration of global legal practices with EU-specific legislation.

Por:

Isabela Burgo – Advogada

Caio Oliveira – Estagiária